Russia failed to take down Ukrainian computer systems with a massive cyber-attack when it invaded this year, despite many analysts’ predictions.

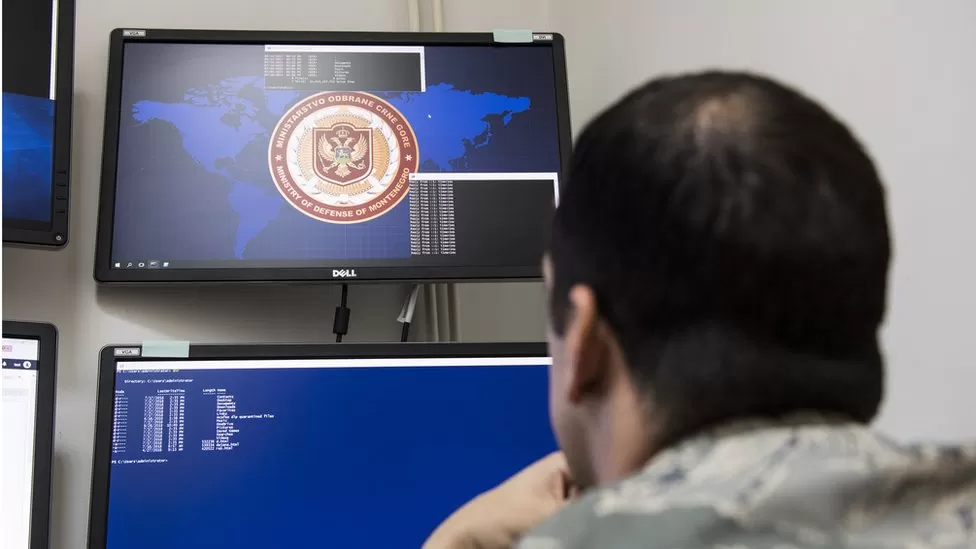

The work of a little-known arm of the US military which hunts for adversaries online may be one reason. The BBC was given exclusive access to the cyber-operators involved in these global missions.

In early December last year, a small US military team led by a young major arrived in Ukraine on a reconnaissance trip ahead of a larger deployment. But the major quickly reported that she needed to stay.

“Within a week we had the whole team there ready to go hunting,” one of the team recalls.

They had come to detect Russians online and their Ukrainian partners made it clear they needed to start work straight away.

“She looked at the situation and told me the team wouldn’t leave,” Maj Gen William J Hartman, who heads the US Cyber National Mission Force, told the BBC.

“We almost immediately got the feedback that ‘it’s different in Ukraine right now’. We didn’t redeploy the team, we reinforced the team.”

Since 2014, Ukraine has witnessed some of the world’s most significant cyber-attacks, including the first in which a power station was switched off remotely in the dead of winter.

By late last year, Western intelligence officials were watching Russian military preparations and growing increasingly concerned that a new blizzard of cyber-attacks would accompany an invasion, crippling communications, power, banking and government services, to pave the way for the seizure of power.

The US military Cyber Command wanted to discover whether Russian hackers had already infiltrated Ukrainian systems, hiding deep inside. Within two weeks, their mission became one of its largest deployments with around 40 personnel from across US armed services.

In January they had a front-row seat as Russia began paving the way in cyberspace for a coming invasion in which Ukraine’s cyber-defences would be put to an unprecedented test.

The infiltration of computer networks had for many years been primarily about espionage – stealing secrets – but recently has been increasingly militarised and linked to more destructive activities like sabotage or preparation for war.

This means a new role for the US military, whose teams are engaged in “Hunt Forward” missions, scouring the computer networks of partner countries for signs of penetration.

“They are hunters and they know the behaviour of their ‘prey’,” explains the operator who leads defensive work against Russia.

The US military asked for some operators to remain anonymous and others to be identified only by their first names due to security concerns.

Since 2018, US military operators have been deployed to 20 countries, usually close allies, in Europe, the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific region. – although not countries like the UK, Germany or France, which have their own expertise and are less likely to need or want outside help.

Most of their work has been battling state-hackers from China and North Korea but Russia has been their most persistent adversary. Some countries have seen multiple deployments, including Ukraine, where for the first time cyber attacks were combined with a full-scale war.

Inviting the US military into your country can be sensitive and even controversial domestically, so many partners ask that the US presence remains secret – the teams rarely wear uniform. But increasingly, governments are choosing to make missions public.

In May, Lithuania confirmed a three-month deployment had just finished working on its defence and foreign affairs networks, prioritised because of concerns over threats from Russia in the wake of the Ukraine invasion.

Croatia hosted the most recent deployment. “The hunt was thorough and successful, and we discovered and prevented malicious attacks on Croatian state infrastructure,” Daniel Markić, the head of the country’s security and intelligence agency, says.

“We were able to offer the US a new ‘hunting ground’ for malicious actors and share our experience and acquired knowledge,” he adds.

But warm public statements mask the reality that these missions often begin uneasily.

Even countries allied to the US can be nervous about allowing the US to root around inside sensitive government networks. In fact, revelations from former intelligence contractor Edward Snowden 10 years ago suggested that the US spied on friends as well as enemies.

That suspicion means the young men and women arriving on a mission are often faced with a stern test of their diplomatic skills. They show up at an airport hauling dozens of boxes of mysterious technical equipment and need to quickly build trust to get permission to do something sensitive – install that equipment on the host country’s government computer networks to scan for threats.

“That is a pretty scary proposition if you’re a host nation,” explains Gen Hartman. “You immediately have some concern that we’re going to go do something nefarious or it’s some super-secret kind of backdoor operation.”

Put simply, the Americans need to convince their hosts they are there to help them – and not to spy on them.

“I’m not interested in your emails,” is how Mark, who led two teams in the Indo-Pacific region, describes his opening gambit. If a demonstration goes well they can get down to work.

Local partners sometimes sit with US teams around in conference rooms observing closely to make sure nothing untoward is going on. “We have to make sure we convey that trust,” says Eric, a 20-year veteran of cyber operations. “Having people sit side-saddle with us is a big factor in developing that.”

And although suspicion can never be totally dispelled, a common adversary binds them together.

“The one thing that these partners want is the Russians out of their networks,” Gen Hartman recalls one of his team telling him.

US Cyber Command offers an insight into what the Russians, or others, are up to, particularly since it works closely with the National Security Agency, America’s largest intelligence agency which monitors communications and cyberspace.

In one case, proof of infiltration came in real-time. One US operator, Chris, who has led multiple European missions, recalls observing someone move suspiciously around the computer network of a partner country.

What was bizarre was that it appeared to be one of the local network administrators the team was working with. That person was standing right behind Chris. Could it be some kind of insider threat?

“Is that you?” Chris asked.

“That is my computer, but I swear that’s not me,” the administrator responded, transfixed as if watching a movie. Someone had stolen his online identity.

“Finding someone on your network is not a good moment especially when they are using your credentials,” Chris recalls. That moment conveyed the reality of the threat and in turn helped secure more access.

The US teams say they share what they find to allow the local partner to eject Russians (or other state hackers) rather than do it themselves. They also use commercial tools so that local partners can continue after the mission is over.

A good relationship can pay dividends. At the end of one mission, US operators say that local partners handed them a parting gift – a computer disc containing malicious software, or malware, from another network the team had not been inside.

Each mission is different and there are some where an adversary has been found on the very first day of looking, explains Shannon who has led two missions in Europe. But it often takes a week or two to unearth more advanced hackers who have burrowed deeper.

A cat-and-mouse game is often played with hackers from Russian intelligence agencies who are particularly adept at changing tactics.

In 2021, it emerged the Russians had used software from a company called SolarWinds to infiltrate the networks of the customers who bought it, including governments.

US operators began looking for traces of their presence. A tech sergeant in Cyber Command who liked puzzles spotted the way the Russians were hiding their code in one European country, General Hartman says. Unscrambling it, he was able to establish the Russians were hiding on a network. Eight different samples of malicious software, all attributed to Russian intelligence, were then made public to allow industry to improve defences.

Hunting is not an altruistic act by the US military. As well as providing hands-on experience for its teams, it can also help at home. In one mission, a young enlisted cyber operator found the same malware they had discovered in a European country was also present on a US government agency. The US has often struggled to identify and root out vulnerabilities domestically, whether in industry or government, because of overlapping responsibilities between different agencies even as it sends out its operators abroad.

Hunt Forward missions are classed as “defensive” but Gen Paul Nakasone, who leads both the military’s Cyber Command and the National Security Agency confirmed offensive missions have also been undertaken against Russia in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine. But he and others declined to provide further detail.

This January, the team in Ukraine were trying to avoid slipping on icy pavements when a series of major cyber-attacks hit. “Be afraid and expect the worst,” read a message posted by hackers on the Foreign Ministry website.

The US team watched in real-time as a wave of so-called wiper software, which renders computers unusable, hit multiple government websites.

“They were able to assist in analysing some of the ongoing attacks, and facilitate that information being shared back to partners in the United States,” Gen Hartman says.

The aim was to destabilise the country ahead of the February invasion.

By the time Russian troops flooded over the border, the US team had been pulled out. Knowledge of the physical risk for their Ukrainian partners who remained weighed heavily on them.

Hours before the invasion began on 24 February, a cyber-attack crippled a US satellite communications provider that supported the Ukrainian military. Many predicted this would be the start of a wave of attacks to take down key areas like railways. But that did not happen.

“One of the reasons the Russians may not have been so successful is that the Ukrainians were better prepared,” says Gen Hartman.

“There’s a lot of pride in the way they were able to defend. A lot of the world thought they would just be run over. And they weren’t,” says Al, a senior technical analyst who was part of the Ukrainian deployment team. “They resisted.”

Ukraine has been subject to continued cyber-attacks which, if successful, could have affected infrastructure. But the country it has continued to defend better than many expected. Ukrainian officials have said that this has been in part thanks to help from allies, including US Cyber Command and the private sector as well as their own growing experience. Now, the US and other allies are turning to the Ukrainians to learn from them.

“We continue to share information with the Ukrainians, they continue to share information with us,” explains Gen Hartman. “That’s really the whole idea of that enduring partnership.”

With Ukrainian and Western intelligence officials expressing concerns that Moscow may respond to recent military setbacks by escalating its cyber-attacks, it is a partnership that may still face further tests.

Source: BBC